“On the eve of the tenth anniversary of 9/11, Monster Children found themselves two blocks from Ground Zero. In a photography studio with a 6-Foot tall By 4-Foot wide Polaroid Camera. In the search for something unique for

of course we had to choose the most expensive of all the ideas. We put the call out to the vast Australian contingency in town for various occasions; Fashion Week a Surf Contest, Movie Premieres and a few that now call the city home. As well we also talked Julian Casablancas to spend his afternoon with us, twelve hours later and at $200 a Shot, the budget was well and truly blown. However what we had produced was both the realisation of a shoot we had wanted to do for years and the process an educational experience.”

Chris on using the camera –

I’d been eyeing off the 20×24 for sometime. So much so, I’d even tried to ship it down to Australia for a project. So when the opportunity to finally shoot in the NY Studios came up, I jumped on it. For me, whenever I saw the images in print or online were always amazing, but it’s not until your actually hands on and involved in the process that it really takes you back to enjoying the Art of Photography. I grew up on the tail end of film and the crossover to digital, so to go back and have to actually think about how you want someone to stand and visualize the final image was so refreshing. I almost wanted to throw my digital cameras out the 3rd floor studio windows. The people I shot were a bit of a mix really. Whether they were surfers, models, musicians or assistants they were all relevant to the youth culture I’m surrounded by I guess. But essentially I just wanted to use the camera on friends that were available that day.

Here Chris talks with Polaroid guru and 20×24 Holdings Executive Director John Reuter about all the intricacies of Polaroid, the technology and who’s stepped in front of the 20×24 Camera.

Using the 20×24 recently was such an amazing way to shoot and really took me back to enjoying the art of photography. Can we first start by asking you to give us a brief explanation of the cameras history?

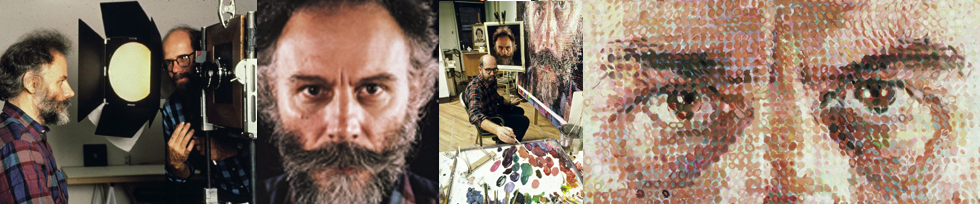

The Polaroid 20×24 Studio had its genesis at the height of the Polaroid Corporation’s reputation as a cutting edge company creating exciting consumer and professional instant photographic products. Edwin Land, the founder ofPolaroid was still very active in the company’s research and development. Riding high on the success of the SX-70 product line, Land and his group turned their attention to the traditional peel apart film that professional photographers used. In the marketplace, a 4×5 inch was the largest film sold, but that was about to change. Polaroid embarked on a program to make the film available to professionals using 8×10 inch view cameras as well as some very specialized larger cameras that Polaroid itself would produce. In the push to create the 8×10 Instant processing system, Dr. Land directed his engineers to push further and called for the creation of a prototype format of 20x24inches. In addition to the 20×24 unit, theresearch group also produced a 40×80 inch camera. This successful reception of large format Polaroid film led to a project to create multiple 20×24 cameras in 1977 and 1978. The research group headed by John McCann built five general purpose 20×24 cameras as well as several others designed for scientific and military use. Polaroid embarked on a program to bring this technology to photographers and artists, allowing access to Polaroid staffed studios in Cambridge and Boston, MA. In exchange for use of the cameras and film, these artists donated a portion of their production to the Polaroid Collection. These artists included Chuck Close, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg.

That’s some incredible history and so amazing that the cameras are still in operation today.Do you know what happened to the 40×80 Inch camera?

The 40×80, created and owned by Polaroid since 1978 was later sold to artist Gregory Colbert, who used it to make large scale image transfers. Artists such as Chuck Close still used it until Colbert dismantled it in 2008. There is no longer any Polaroid film for it.

For people that aren’t familiar with the operation and mechanics of the camera can you give us an insight into how the camera works and produces such a large format Polaroid ?

It is remarkably similar to any peel apart process. The negative gathers the light on silver crystals and transfers the image information directly (BW) or through dye developers (colour) that migrate to the positive material once activated by the reagent, which activates the silver or dye developers present in the negative and begins the diffusion transfer process. In 20×24 the processing machinery is contained in the back of the camera. with a pair of motor driven 22- inch rollers. The film is in roll form and each individual exposure is cut off as it exits the processing rollers, setting up the camera for the next exposure.

Has the film always been made by Polaroid? And when they announced they were ceasing production on Polaroid film, how did that effect the operation?

The film has always been made by Polaroid. All of the stock they manufactured was always large, 44 inches for the positive and 60 inches for the negative. The trick was picking Out the cleanest and best performing sections of a

given base roll and then optimizing a reagent for the selected cut. We knew as early as 2004 that Polaroid would be exiting the film business and planned accordingly. Initially it led to increased business, despite our assurances that we were not going away. And how many 20×24 cameras that you know of are alive and working right now? There are six working all in one” cameras, the five original production models and one hybrid, based or) an early prototype and a new front end. There are also over a dozen field cameras with removable cassettes made by the Wisner Company. Unfortunately, they were not well designed or manufactured, and all but one are not in use today. 20×24 Holdings have commissioned Mammoth Camera in California to build 2 new units, which we expect to be completed by the end of the year.

How did you come to work with the 20×24 camera – it wasn’t a planned out career path right? More something that you fell in to? I was an artist who used Polaroid film for my work in graduate school at the University of Iowa in the late 70’s. Upon receiving my Master of Fine Arts degree, I expected to teach on the university level. When that did not happen, I interviewed at Polaroid for 2 jobs, one a research studio and the other the 20×24 studio, which was just starting up in the fall of 1978. I was actually not interested in the 20×24, I much preferred the research photography position and in fact accepted that, even though I was offered both jobs. After a year a half, the position became open again and this time I accepted.

Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Julian Schnabel have previously used the 20x 24 Polaroid Camera for creative projects. Can you share an insight in to working with such artists?

I was present when Andy Warhol was photographed; I would not characterize his session as “working” with the camera. I adored Robert Rauschenberg and my time with him was very special, although he was distant from the actual production. Julian Schnabel was perhaps the most impressive, fearless in his use of the machine, going against all expected use of the medium. It is always a privilege to work with such accomplished artists, and you feel pride that you can bring the most of the experience of the camera to take advantage of their vision.

Are we right in saying that the highest price paid for a Polaroid was of Andy Warhol for $254K?

I guess there’s plenty of interest and intrigue surrounding Warhol. Honestly. I was not a fan then. I felt it was a superficial session, it only lasted a half hour. My opinion of Warhol changed greatly when I visited the Warhol museum in 1997. I did not regard him as a serious artist until I saw his early work.

Can you give us an insight into the shoots you were present on with him?

I really felt that he was barely there, he was incredibly guarded, a prisoner of his fame.

Lady Gaga, Presidents, film stars…there is a long list of identities who have posed for the camera. Who else has found themselves in front of the lens of the 20×24 with you?

My favourites: Bill Clinton. Hillary Clinton, David Byrne. Alec Baldwin, Chris Rock. Spike Lee, Ringo Starr. Paul Simon, John Malkovich, Jodie Foster, Susan Sontag. Al Gore. Sting, Danny DeVito. Dalai Lama, Bill Bradley, just to name a few.

And what about photographers – who are some photographers that have used the 20×24 over the years?

Again, some of my favourites: Tim Burton, Robert Wilson. Chuck Close, Mary Ellen Mark, Bill Wegman, David Levinthal, Timothy Greenfield- Sanders , and Joyce Tennseon.

Where are the more adventurous places the 20×24 camera has found itself?

Death Valley, the swamps of Hilton Head,South Carolina. Hotel lobbies in old Miami Beach and the forests and lakes of Maine.

And what’s one of the more outrageous things you’ve witnessed being shot?

You know I cannot tell the truth about that.

If you could have one 20×24 Polaroid on your wall from over the years which would It be?

I have several, images of my children. Hands down.

Interview reproduced with permission of Monster Children, may not be reused without permission.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)