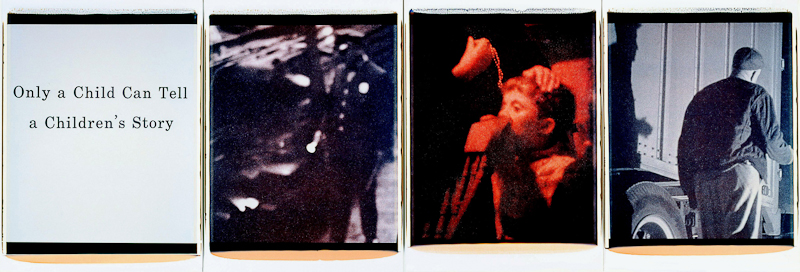

From the 20×24 Archives, Jack Butler’s provocative exhibit from 1991:

My childhood serves as the experience for the emotional and psychological foundation of this work. Each piece is physically made up of four 20 x 24 Polaroid photographs. The images suggest “instant photograph” yet the scale and content deny that fact. Each piece is intended to pose a question, “to what extent have we internalized the rationalizations of false hope and expectations, and with them, the self-victimization that entails” and how does this manifest itself now in our current social existence.

The work has been critically described as “a valuable contribution toward demystifying a social climate in which a “return to family values” has coincided with an unprecedented and unimagined trend toward domestic maladies” and “opening the tightly sealed Tupper-ware world of socially supported physical and psychological violence within the American family”.

JACK BUTLER

at Fahey/Klein and in With the Media, Against the Media at the Long Beach Museum of Art

These pieces represent a sustained attack on what Foucault has called “the government of individualization,” that is to say, those social practices that impose a determination on the individual and tie him or her to a constraining identity. In juxtaposing images and text, Butler draws out the operations of “disciplinary technologies” within the workshop of the home, in the production of the “docile body” (in both genders, as he points out, and with special emphasis on childhood and adolescent development) concurrently with the “productive body” (both sexually as well as materially). The texts are imbued with a contemporary banality (The Mind of a Failed Father ) and must be read not as illustrative of the images, but as equally symptomatic of the strategies of, rationalization in relation to excesses of power. Overall, Butler’s work makes a valuable contribution toward demystifying a social climate in which a “return to family values” has coincided with an unprecedented and unimagined trend toward domestic violence and homicide.

—G. Daniel VenecianoYou can see more of Jack’s work at Jack Butler’s Art.