In 2013 artist Jeff Enlow approached the 20×24 Studio with the idea to expand his project “Parallelograms” to the 20×24 format. Jeff had been working for some time in 4×5 format and dreamed of scaling it up to the pinnacle of the large format instant experience. After a half day test session to be sure it would work Jeff embarked on a Kickstarter campaign to fund further shooting sessions. This was the first Kickstarter we know of to underwrite a 20×24 project and the response was enthusiastic. With the Kickstarter proceeds Jeff was able to fund several more sessions, completing his vision for the Parallelograms series with a flourish.

In 2013 artist Jeff Enlow approached the 20×24 Studio with the idea to expand his project “Parallelograms” to the 20×24 format. Jeff had been working for some time in 4×5 format and dreamed of scaling it up to the pinnacle of the large format instant experience. After a half day test session to be sure it would work Jeff embarked on a Kickstarter campaign to fund further shooting sessions. This was the first Kickstarter we know of to underwrite a 20×24 project and the response was enthusiastic. With the Kickstarter proceeds Jeff was able to fund several more sessions, completing his vision for the Parallelograms series with a flourish.

Behind the scenes photos by Bryan Derballa.

Jeff writes of his experiences with the 20×24:

I first discovered the 20×24 as a young student flipping through an American Photo Magazine. There was a small feature on the camera at Sundance. I remember being amazed by the size and weight of the camera. I always loved instant film but this was something else all together. At that time in my life using the 20×24 camera was well beyond my means or skill level. I stored the idea in the back of my mind till I had a project that called for the camera.

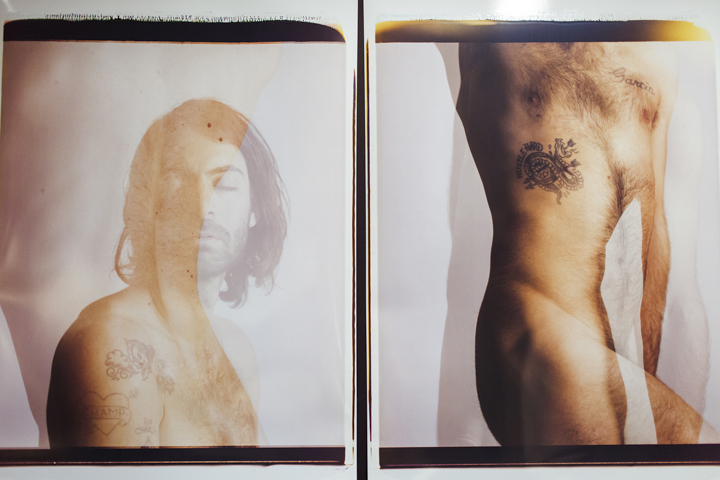

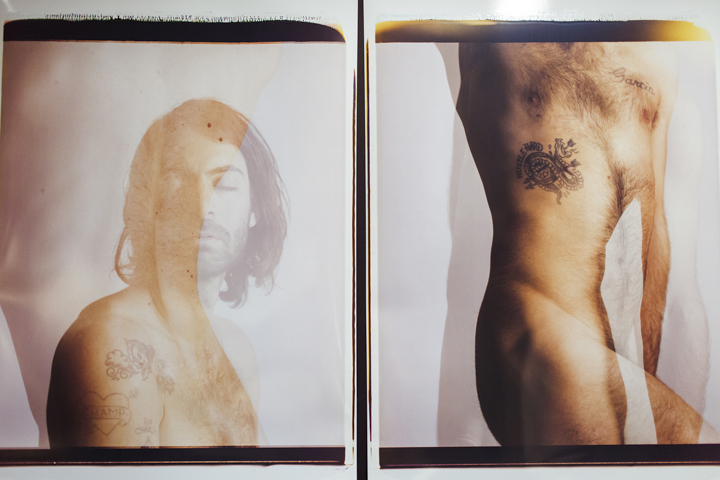

When I first conceived of Parallelograms, central to the project was that the images had to feel physical. I wanted to make an image that felt more like making a painting. There is a certain draw to seeing an original one of a kind painting in a museum or gallery that I felt is lacking in photography. Shooting on instant film became the bridge between those two mediums.

Visually, Parallelograms is a study of the topography of the human body. Multiple exposures allow the eye to wander in and out of the intersecting and diverging hills and valleys of the human figure. The unexpected shapes that are revealed in the merging of the two exposures is a wholly new creation—a sacred third entity—that exists in no other plane but on that single instant film sheet.

I start with a general sketch of an image in my head and first shoot it on 4×5 Fuji pack film. I collaborate with the model and decide the basic structure and flow I am looking for. From there, there are lots of micro adjustments like “drop your chin down, pull this arm back, hide that piece of hair;” I shoot one exposure, then we reset and do it all again. I mark on the ground glass the outline of the first image; so that when we shoot the second image I can try and guide it to flow well. I can steer the image in the direction I want, but the final print has a gestalt that is beyond omniscience.

There is a bit of translation that happens between shooting on the 4×5 and the 20×24. Using a medium as big as the 20×24 I had to rethink my relationship with both the model and the camera. I couldn’t just show up and reshoot my existing 4×5 images. I have a greater level of flexibility in the smaller 4×5 camera. I can push the camera into different positions and angles that aren’t possible when you are working with a camera a 1000 times larger.

Despite having this massive impedance between the model and myself I was able to achieve an intimacy on the 20x24s that I hadn’t reached before. The intense detail captured transforms the photos into truly rich character studies. It takes a lot of bravery for a model to stand nude in front of the camera. There is little you can hide from a 20×24 Polaroid, every freckle, blemish, and hair is exposed and enlarged.

Using the 20×24 forced me to dramatically slow down. Because of the size and complexity of the camera, along with the rarity and cost of film I only shot 10 – 12 images in a day. This makes little room for error, but also makes for an interesting and nuanced edit of the images. Additional versions of the same image are presented next to one another to highlight the subtle shifts that happen while shooting.

Working with the 20×24 Polaroid creates a craftsmanship to each image that elevates the photo beyond just the culmination of pigments in emulsion. Like brushstrokes on a canvas, subtle details reveal the hidden history of each image. The temperature and humidity in the room, the age of the film and camera, the motion of how the emulsion is pulled—all these elements combine to make a final image that has a visual language and personality unique to itself.

.jpg)

In 2013 artist Jeff Enlow approached the 20×24 Studio with the idea to expand his project “Parallelograms” to the 20×24 format. Jeff had been working for some time in 4×5 format and dreamed of scaling it up to the pinnacle of the large format instant experience. After a half day test session to be sure it would work Jeff embarked on a Kickstarter campaign to fund further shooting sessions. This was the first Kickstarter we know of to underwrite a 20×24 project and the response was enthusiastic. With the Kickstarter proceeds Jeff was able to fund several more sessions, completing his vision for the Parallelograms series with a flourish.

In 2013 artist Jeff Enlow approached the 20×24 Studio with the idea to expand his project “Parallelograms” to the 20×24 format. Jeff had been working for some time in 4×5 format and dreamed of scaling it up to the pinnacle of the large format instant experience. After a half day test session to be sure it would work Jeff embarked on a Kickstarter campaign to fund further shooting sessions. This was the first Kickstarter we know of to underwrite a 20×24 project and the response was enthusiastic. With the Kickstarter proceeds Jeff was able to fund several more sessions, completing his vision for the Parallelograms series with a flourish.

.jpg)