20×24 Studio FAQs

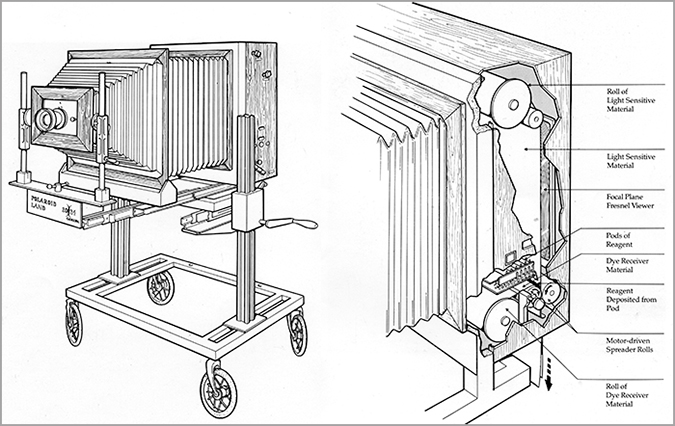

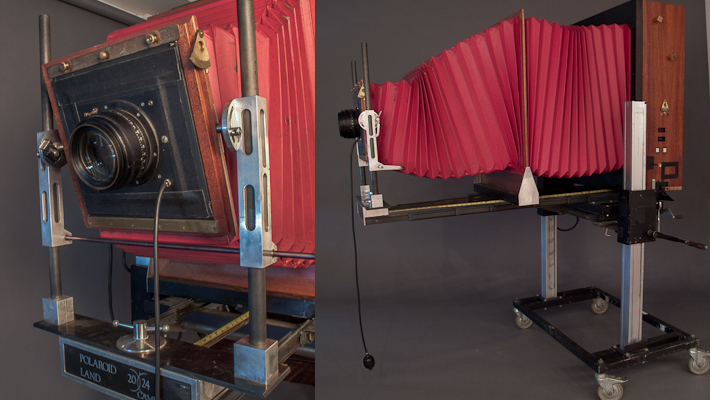

What are the specifications of the camera? The 20×24 camera is a traditional view camera, but has hybrid characteristics of a rail camera and field camera. It weighs 235 pounds and sits on a rectangular frame on wheels that supports a two-column studio stand. The bellows is driven by a telescoping nylon gear that allows bellows extension from 17’’ to 60”. The front standard has 24” of rise and fall, 6” of side to side shift and the ability to swing 4” forward and back. The rear standard of the camera is static and has no independent rise and fall separate from the camera itself. The camera can descend to 24” and rise to a height of 72”. The camera rear box contains a built in processor with 22″ titanium rollers. It is driven by a geared motor drive powered by a 110v AC motor. Transformers are used for 220 or 240v current.

What kind of lenses does the 20×24 Camera use?

You can use any number of lenses on the 20×24 Camera. The New York studio offers a 1200, 800, 600, 360, 210, and 135mm lenses. The 1200, 800, and 600 were designed for 20×24 format, but the other lenses are for 8×10 and 4×5 formats. The bellows extends from 17 to 60″. A 1200mm lens is 48″ and can pretty much only be used outdoors. The 800, or 31″ provides a bit of a telephoto look and can render images from infinity to nearly life size. The 600 or 24″ has the most range, going from infinity all the way to 1.5 times life-size. The 360, or 14″ can provide magnifications of 1.5 times life size to almost 4x life-size. The 4×5 lenses allow extreme magnifications of up to 10X. As magnification increases, depth of field decreases, as does subject to lens distance. This makes lighting more difficult, as there is much less room to insert lights and the bellows factor of light loss can reach up to 8 stops. The shorter focal length lenses will give a wide angle effect, using the 360mm will provide a similar distortion to a 24mm lens on 35mm film format.

How does the 20×24 instant process work?

The 20×24 format utilizes the exact same material that Polaroid once produced for all peel apart films from 3 and ¼ by 4 ¼ inches up to 8×10. There were three distinct film types, Black and White, a silver only emulsion and two Color emulsions, Polacolor ER and Polacolor 7. In black and white film the image formation is accomplished through a transfer of undeveloped silver halide, unoxidized developer, and unused alkali to the receiving layer. Once in the receiving layer, the chemicals react to create a positive silver image. The Black and White film that is used in 20×24 is known as “Coaterless”, and does not require the print coater solution that earlier films such as Type 52, 552 and 57 did. The physical makeup of color instant films contains many more components than found in comparable black and white films. The basic structure consists of a black support material holding separate silver gelatin emulsion layers sensitive to red, blue, and green light. During processing, each of these will form its own separate color record as it releases a complementary subtractive dye (the red-sensitive layer releases cyan dye, the blue-sensitive layer releases yellow dye and the green-sensitive layer releases magenta dye). In between these color layers are spacers that contain alkali-diffusible dye developers. Above these dye and spacer layers sits the image-receiving layer, followed by a timing layer that consists of both a barrier and an acid. Lastly there is an acidic mordant layer that will fix the dyes in place. The layers are arranged as such to facilitate the chain reaction that takes place during development.

The developer pod in instant color materials contains a strong alkaline reagent in gel, usually made of sodium or potassium hydroxide. The reagent has been made viscous by water-soluble polymeric thickeners and also contains high molecular weight polymers, reducing agents, alkali,as well as components that assist in image formation and stabilization. The pod itself must be inert to strong alkali and able to keep out oxygen and water for long periods of time. The process used by Polaroid known as alkaline induced dye diffusion transfer is outlined here. After the alkaline developing reagent has been spread over dyes, it forms a uniform layer that serves as a “protective colloid” during

processing. (The reagent is spread above the light sensitive layers and below the image layer.) The developing reagent then begins to migrate toward the receiver sheet. While the reagent moves, it changes the exposed particles in each layer into metallic silver. It then dissolves the three developer dyes allowing them to diffuse from their original locations toward the receiver sheet. As the dyes move they are blocked wherever the metallic silver exists. Only dyes from the unexposed areas of the film will reach

the receiving layer to produce a positive color image. At the same time the developing reagent is moving down toward the light-sensitive layers, it is also diffusing through the timing layer to eventually come in contact with the layer of acid. Here the acid and alkaline combine to form water and salt. In some types of instant color film the developing chemicals may remain on the surface of print while in other cases

they are pulled off and discarded. Thanks to Annie Walker of the University of Texas in Austin for her in depth interviews with Polaroid scientists to produce the above information on the film technology. You can find her entire paper here.

How is the film put in the camera?

20×24 film is provided on rolls. The negative is supplied as a 150’ roll and sits on brackets at the top of the camera box. The positive is on a 50’ roll and sits on a similar bracket at the bottom of the processor. There are no sprockets in the film and it is moved into position with tab connected to string with adhesive tape. This simple solution was utilized early on and has never been improved on. Above the positive roll in the camera sits a tray that through a chain driven system moves the chemical reagent pods into position between the two rollers where the negative and positive meet.

The 20x24 Camera and Processing Back

Camera in Tilt Mode/ Bellows extended

Camera in Swing Mode/ Processing Back

Ted McLelland, John Boudrow, Rob Young and Tom Silva, are Team 20x24 Holdings. They are shown here with the reagent reactor.

What is a pod? A pod is a foil packet with special seals designed to break under pressure when passing through rollers, allowing the reagent to spread evenly between the negative and positive rolls and begin the development process.

How are the pods made? The pods are produced on a special machine, the only remaining one in the US (Polaroid nice had dozens of pod machines in their US factories). It is housed in our warehouse in Putnam, CT.

The Pod Machine, built in 1956 in 20x24 Holdings Putnam, CT facility.

Will you ever produce your film in smaller format? That is something we are actively looking into.

Here is a video on the pods being made in 2010. Roy Johnson, Marc Soufrant, and Ted McLelland produced the run.